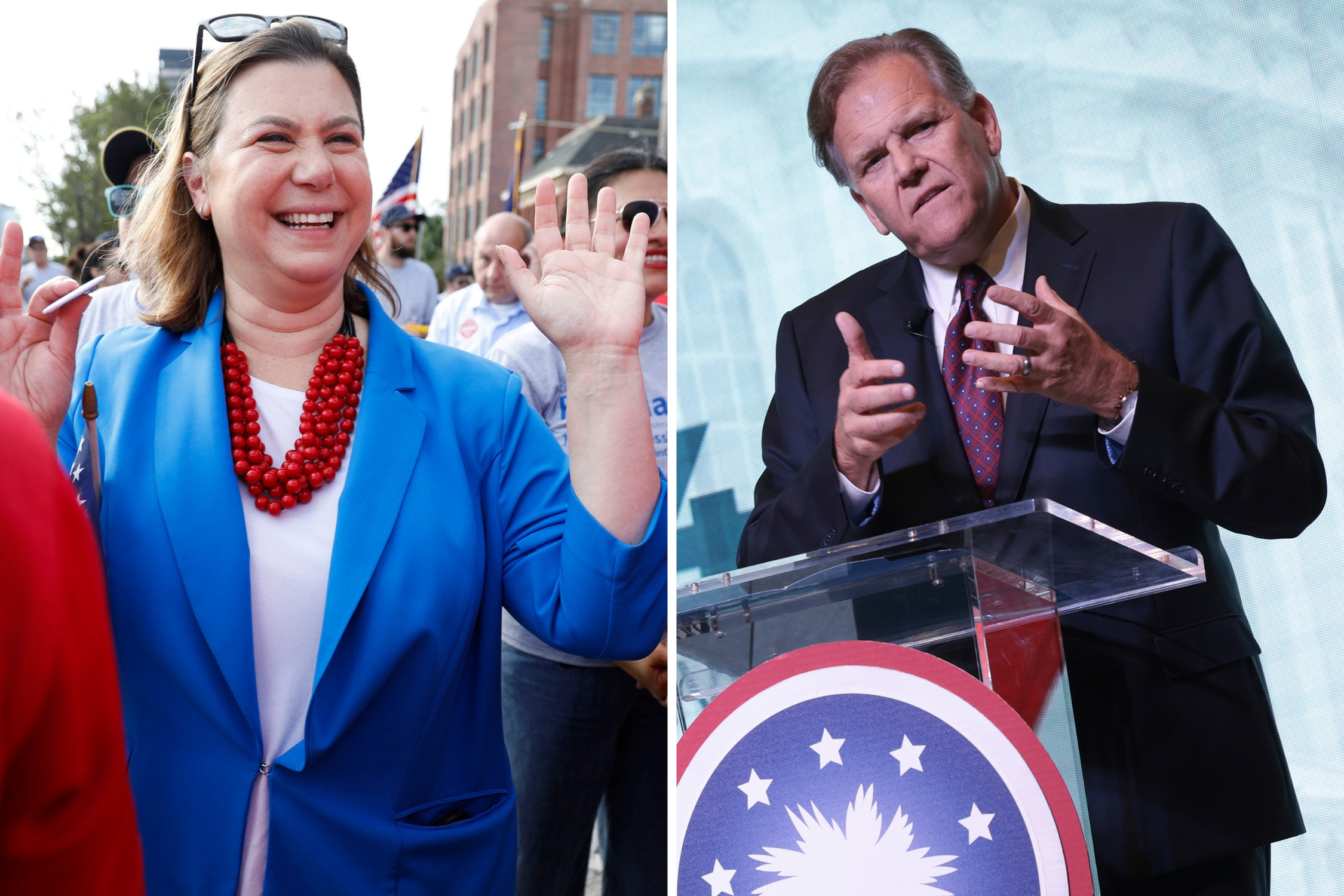

On the same mid-March night that Bernie Sanders' presidential ambitions were snuffed out, the movement for which he is an icon also happened to enjoy perhaps its most significant triumph. The voters in Chicago's suburbs who backed former Vice President Joe Biden by more than 20 points over the Vermont senator for the top of the Democratic ticket also traded in their eight-term congressman, Rep. Dan Lipinski, for 55-year-old abortion-rights activist Marie Newman.

Newman ran on a campaign of Sanders' greatest hits—Medicare For All, a $15 minimum wage, the Green New Deal, free college, the abolition of ICE—and is a shoo-in to win in November.

Her victory, more even than other prominent Sanders disciples who have attained federal office since Sanders' unexpectedly competitive 2016 primary run, represents a substantial leftward shift for the Democratic caucus. She replaces a significantly more conservative Democrat who voted against the Affordable Care Act, and now she's poised to occupy a safe seat for a long time.

Many observers point to Sanders' inability to crack 35 percent among Democrats in most of the 27 states and territories that voted in 2020 (before the COVID-19 pandemic short-circuited the process) as proof that his ideas are not as popular as he proclaims. But that's not the whole story. It's true that most of Sanders' proposals remain light years from the sort of popularity required to get them through Congress, even if Democrats retake the Senate and White House, and doubters make a strong argument that the failure to become law means Sanders wasted everyone's time and attention with unworkable solutions to serious problems.

But there are other signs—like Newman's victory and some recent policy shifts by the now-presumptive Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden—that suggest the Sanders movement is simply outgrowing its need for Sanders himself and his purist approach.

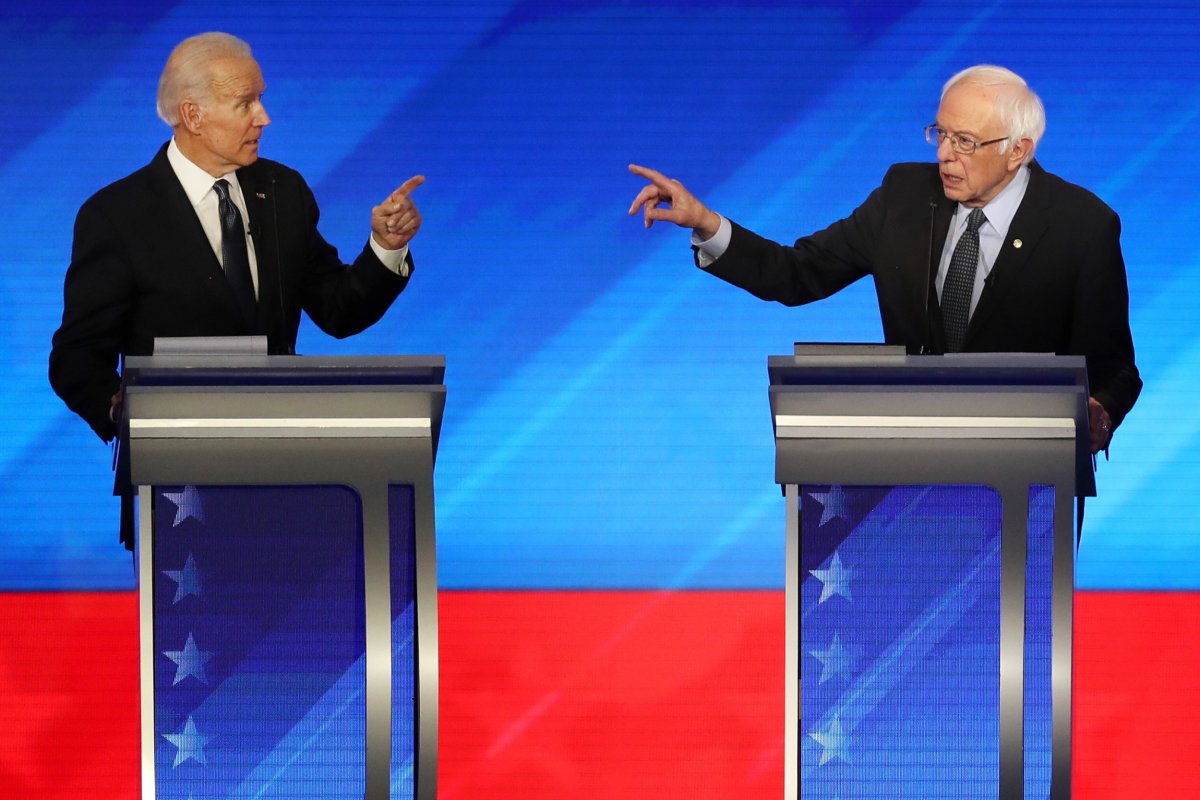

Sanders all but acknowledged as much after Newman's victory and his shellacking in the Illinois, Arizona and Florida primaries on March 17, emailing supporters the next day to say, "While our campaign has won the battle of ideas, we are losing the battle over electability to Joe Biden." He hammered the point even harder Wednesday as he announced he was suspending his campaign: "It was not long ago that people considered these ideas radical and fringe. Today these are mainstream ideas and many of them have already being implemented in cities and states across the country. ... The future of this country is with our ideas."

The 78-year-old Democratic Socialist will almost certainly never become president of the United States—but that's largely irrelevant. It many ways it is Bernie Sanders' Democratic Party now—an irony, given that he has never joined the party—with all of the major presidential contenders in the 2020 cycle supporting some form of expanded or universal health insurance coverage, efforts to make college affordable and aggressive new actions to slow or reverse climate change. "Bernie Sanders might not end up being the nominee, but he has pushed almost every major candidate this cycle, including Joe Biden, to adopt his policies and vision for what the president should do," says Stephen O'Hanlon, the 24-year-old spokesman for the Sunrise Movement, an environmentalist group that helped Sanders and Sanders acolyte Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez write the Green New Deal. O'Hanlon says he became interested in politics through the 2016 Sanders campaign.

Biden echoed this notion himself in a Medium post appealing to Sanders fans to support his effort to unseat President Donald Trump: "Senator Sanders and his supporters have changed the dialogue in America. Issues which had been given little attention—or little hope of ever passing—are now at the center of the political debate. Income inequality, universal health care, climate change, free college, relieving students from the crushing debt of student loans. These are just a few of the issues Bernie and his supporters have given life to." Even before Sanders quit the race, the former vice president had softened his opposition to universal free college, a signature Sanders proposal, by coming out in mid-March for eliminating tuition at public universities for students from families making less than $125,000 a year. Biden had previously supported only free community college.

"Sometimes getting elected is beside the point," says Gordon Weil, former press secretary to Democratic Sen. George McGovern, who was demolished by Richard Nixon in the 1972 election. "The movement, to the degree it was concerned about getting Bernie elected? Sure, it's hurt. He's not going to be elected president. I don't think he was ever likely to win the election. And I don't think that undermines the success or the influence of his ideas. He's very influential. He doesn't need to go back to the Senate feeling, 'Well, I didn't do anything for having run twice.' He did do something."

There are, of course, many Sanders skeptics who believe, as Bill Scher wrote in POLITICO Magazine on Wednesday, "It's hard to see Sanders' presidential campaign as anything other than a defeat." Democratic primary voters, in choosing Biden, were rejecting several specific Sanders proposals, from Medicare For All to certain elements of the Green New Deal, even as they were broadly supportive of both universal health coverage and aggressive action to combat climate change, Scher argued. And even Biden, while offering respect and admiration for Sanders' movement, stopped short of endorsing any of its dogma. "While Bernie and I may not agree on how we might get there, we agree on the ultimate goal for these issues and many more," wrote Biden, avoiding explicit commitment to a Sanders solution.

Sanders progressives have plenty of work left to do before they can really declare victory, and some of what happens next for them depends on which historical precedent the Sanders movement follows. Will it be that of Arizona Sen. Barry Goldwater, the aggressively small-government Republican crushed in the 1964 election, or McGovern, who loomed large for young voters as an icon of the anti-Vietnam War effort? Both men, like Sanders, drew legions of young intellectuals into their political camps—but Goldwater partisans built a durable infrastructure of think tanks like the Heritage Foundation and publications like National Review, and seeded the Republican Party with devotees. Eventually, those low-level party functionaries took control and helped another charismatic leader, Ronald Reagan, make the Goldwater creed broadly popular with the mainstream.

McGovernism, however, faded into the background after the war ended. Many former McGovernites did remain in politics—Bill Clinton was his campaign manager in Texas—but the party itself moved to the center and consigned the failed candidate to a past it needed to overcome, Weil says. University of Virginia post-doctoral fellow Joshua Mound, a Sanders supporter and frequent writer for the democratic-socialist journal Jacobin, sees the Goldwater model at work in the Sanders legacy.

"If you listen to or read about the personal narratives of people like Karl Rove, they were teenagers who really became engaged by the Goldwater movement and became true Goldwater believers, and that's what got them involved in politics and wanting to take over things like the College Republicans," Mound says. "You're seeing that with Sanders because it's gone beyond just being about Sanders: it's about him and the young people who were pretty disenchanted with politics and who now see a model of politics and a set of idea that they believe in. That has pushed some of them to run for offices and get involved in grassroots politics in a way that's hard to see them doing absent Sanders' 2016 run."

Several organizations and media outlets have been founded or boosted by veterans of Sanders' 2016 effort. Besides Jacobin and the Sunrise Movement, there's also the activist group Indivisible as well as progressive political action committees Our Revolution, Democracy for America and Justice Democrats. "There was not an organized Socialist movement before Bernie's campaigns," says Meagan Day, a leader of the Democratic Socialists of America, which grew from 6,000 members in 2016 to about 60,000 now. "It really was Bernie's willingness to say, 'I am a Democratic socialist' in 2016 and to run on a platform of Medicare For All, environmental justice—what we now called the Green New Deal—college for all and so many other demands that center people over profit, that showed people that there was another political tradition that did really value people and workers."

But even some liberal activists warn that the notion that Sanders' policies are now mainstream—as he declared in his statement Wednesday—may not yet be true. Sean McElwee of Data For Progress, a think tank aiming to provide the intellectual underpinnings for progressive arguments and generating polling data to aid with electoral strategies, says Sanders misunderstood his own 2016 popularity as an endorsement for "very liberal economic and social policies" when it appears to have been largely a reaction to Hillary Clinton's personal unpopularity. Polls show Medicare For All is only narrowly popular and loses support when some details, such as the loss of private health insurance, become known to voters.

"You had a sea change between the 2018 Congress and the 2010 Congress. I think every Democrat elected last cycle with very few exceptions supported a public option for health insurance at minimum, and some would say their goal ultimately is to eventually get to a Medicare For All plan," McElwee says. "It would be unfair to say Bernie gets no credit for that. But Sanders has too expansive an agenda to ever be fully passed. The question is, who actually makes the deals to get some of that across the finish line and where will Sanders be when those deals are made."

That Sanders managed to attain this level of prominence in the first place was a surprise in and of itself. For most of his career, he was seen as an eccentric, fringe player, a peculiarity with his antipathy for capitalism, whose Bernifesto about the ills of the nation barely changed from the talking points that he used to get elected mayor of Burlington, Vermont. His campaign in 2016 seemed to exist to shove Hillary Clinton to the left but found real traction with a generation of new adults drowning in student debt and struggling in careers stunted by the Great Recession. To them, this cranky, unvarnished, wild-haired messenger's long history of espousing his ideas felt authentic and appealing where Clinton's more cautious approach felt focus-group-tested and insincere.

"Bernie is singular in America political history in his consistency and history," says Abdul El-Sayed, 35, who ran unsuccessfully for Michigan's Democratic gubernatorial nomination in 2018 as a Sanders-endorsed candidate. "He's been on this page since before I was born. He's been able to cut through a lot of the noise to talk consistently, forthrightly and loudly to a generation for whom the private sector has failed over and over and over again. He comes through that with his integrity intact, with a clairvoyance of moral perception of this moment and what's required. You're going to follow that person."

This is where victories like those of Newman, Ocasio-Cortez or Rep. Ayanna Pressley of Massachusetts come in. Sanders skeptics within the Democratic Party argue that the party retook the House in the 2018 midterm elections by putting forth palatable centrist candidates in competitive Republican-leaning districts who would never have won on a Medicare For All message. But Mound says that's a short-term view: it's those Sanders-esque leaders who can count on winning easily over and over who will eventually come to rule the party itself.

"Taking over the party in terms of progressivism really isn't a contest of winning swing districts with left-leaning people or even the presidency," Mound says. "It's really about winning over safe districts with the Sanders platform and building a durable party infrastructure of elected officials who are always going to win their election and always going to in leadership."

Eventually, though, the Sanders movement will need a Reagan, a figure so personally popular and politically effective as to persuade nervous moderates of the righteousness of these ideas, McElwee says. Ocasio-Cortez seems poised to be a long-term presence, although she upset purists in February by suggesting compromises may have to be made on the road to Medicare For All; two other below-the-radar Sanders disciples include New York State Sen. Julia Salazar and Virginia state Delegate Lee Carter, both avowed Democratic Socialists who surprised many by winning office in recent years.

"There are a lot of young leaders in the progressive movement," O'Hanlon says. "Our generation is running for office thanks to Bernie, they're taking politics seriously and they're ready to fight for the soul of this country. I don't think we have any shortage of new people to carry this fight forward."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.